In April 2019, I came down with a nasty case of vertigo. The acute phase lasted a month, and after that it would come and go, never reaching the original peak but also never recovering fully. After a long journey with several specialists, an otolaryngologist at Johns Hopkins cracked the case, and my Vertigo journey ended. Mostly. Along the way, I learned a surprising amount of fun science. In this blog post, I’ll share a bit about those learning and how this disease felt.

The symptoms

The main symptom of vertigo is the spinning and dizziness. Being dizzy can be fun for a while, but of course it gets old quickly. The chronic dizziness of Vertigo makes it difficult to work or care for kids. Driving was impossible.

"Thanks, I hate it" is the correct reaction.

Even when the world was not spinning, my head never felt fully fixed in space. The sensation is hard to describe - imagine objects in the distance always vibrating just a little bit.

The last symptom I felt is much harder to describe. It’s something like electrical noise or static. There’s no actual sound, though, or any other feeling I can easily compare it to without sounding a little crazy. Imagine a beam of television static blasting from a spot at the back, left side of your head. The doctors didn’t say that other Vertigo patients had something similar. But for me, it came with the Vertigo and left with the Vertigo.

The inner ear

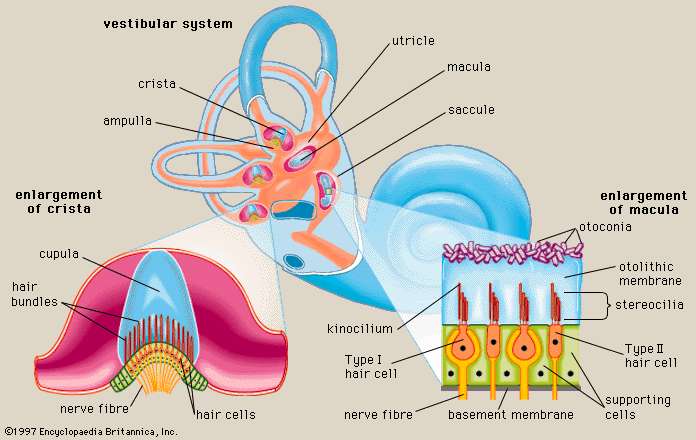

Let’s see what broke. Hair cells in the cochlea that are excited by the fluid oscillations caused by sound waves, letting us hear. The vestibular organs contain the same type of cell responding to a different fluid movement - the movement of fluid rotating in the semicircular canals in response to head rotation.

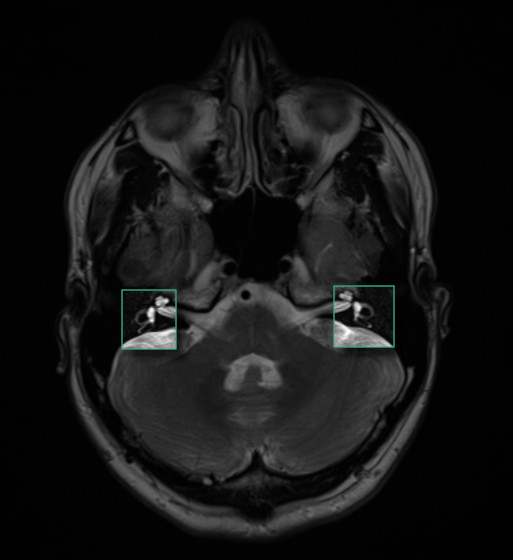

The semicircular canals are large enough to see in an MRI scan. If you’d like to see my semi-circular canals, feast your eyes.

To detect static head orientation, we need to make use of gravity. In the inner ear, we see these same cells again, now embedded in jelly and capped by heavy calcium crystals called otoconia. As a head tilts one way or the other, these crystals shift their position, activating sets of hair cells sensitive to that particular tilt.

Trouble in inner-ear paradise

There is no physical barrier between the otoconia crystals in their jelly, and the fluid of the semicircular canals.

Like any open office plan, this setup has problems. The otoconia crystals sometimes dislodge from their jelly and float into the semicircular canal. The heavy crystals interfere with the motion of the fluid in the canals during head rotation, producing out-of-whack rotation signals.

One weird trick…

Here is an idea so crazy that it just might work. We know the shapes of the semicircular canals, we know where otoconia are supposed to live, and we know that otoconia fall under the influence of gravity. Maybe we could rotate the head through a series of positions to guide the otoconia back to their jelly?

One of my complaints about science is that our elegant models tend to fall over in the face of real world complexity. But in this case, the model does work, and a large number of Vertigo cases can be cured exactly this way. That’s one of the things I was most delighted by in this whole journey.

Loose crystals from one sensory organ tresspassing into the working end of another sesnory organ is a simple model. What made my vertigo story so delightful to me was the way the model works in practice, to suggest a cure that requires no drugs or prolonged therapy. The treatment is called the Epley Maneuver.

If (a) crystals can get into the semicircular canals, (b) this cause problems when crystals move and interfere with fluid sensors and (c) the shapes of the canals are well known, then perhaps by rotating the head a certain way we could coax the crystals back through the canals and into the utricle where they belong, a bit like the toy with a marble navigated through a maze on a balance board you control with knobs?

Well, for that subset of vertigo cases where loose crystals are the cause, it does work. And one has to wonder, when Epley first tried it successfully, was this a Eureka! moment for him, or with total confidence in the crystal hypothesis did he shrug the maneuver’s success off as trivial.

When the right side (most commonly, the hindmost of the three canals) is the problem, the crystals tend to settle at a low point in the ring, and we want to get them around the top of the ring and back into the utricle. The maneuver goes like this:

- Sit straight up

- Turn the head 45 degrees to the right

- Keeping the turn, lay back fairly quickly, letting the head hang below the sholders

- After the nystagmus subsides, remain lying down and turn the head toward the opposite side

- After the next wave of nystagmus subsides, roll onto your left side, keeping your head turned toward your left shoulder

- After the next wave of nystagmus subsides, lift your body to a sitting position

To see why this works, try the procedure on the model head below. The model has two loose crystals in his right canal. The controls are tricky, but if you get the sequence right, they will land on the green “utricle” and be stable there as long as the head stays upright.

If the head can bec back to the upright position without the red crystals falling back down, you win!

Feels

As you can see in the simulation, when the head is still, gravity brings the crystals to their lowest location. A few minutes after lying down in bed, things in the inner ear are settled down. The fluid motion sensors are not being activated. Everything feels back to normal.

Being still in bed is so comfortable, in fact, that you can start to wonder if the whole condition is clearing up and you can go back to normal activities soon. But, for quite some time, sitting up very reliably brings back the vertigo and all the discomfort. This ends up training you not to leave the bed, to spend a long time after waking up in an anxious state, temporarily cured and hoping that you will still be ok when you get up, but knowing that probably won’t happen. It’s emotionally hard, and during this episode, I gained a ton of sympathy for people with chronic illness.

Treatment

Here is a rough breakdown of the medical care I received, with the cost after insurance.

| Date | Center | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| 2019-06-02 | Urgent Care | $150 |

| 2019-06-02 | Union Memorial Hospital | $800 |

| 2019-06-20 | Mercy Otolaryngology | $100 |

| 2019-07-20 | Mercy Neurology | $150 |

| 2019-08-02 | Mercy Radiology | $150 |

| 2019-12-03 | Hopkins Otolaryngology | $100 |

The first two trips happened because the dizziness came on so strongly that my wife and I thought there may be a serious issue. Urgent Care also didn’t want to rule anything out, and they urged us to go to the ER (it was fairly late at night, and I couldn’t reach my family physician).

I was perscribed nausea medicine and told that I probably had viral labrynthitis, which should resolve itself it 3 to 14 days. While the strongest phase did die down after a couple of weeks, I had the residual feelings mentioned above. They could come and go, maybe once a month I had a week of symptoms.

So I kept seeing other specialists. An otolaryngologist at Mercy Medical agreed that it was viral labrynthitis and prescribed low-dose valium and waiting. We decided not to take the valium - due to the wait times before our visits, the visit tended to happen on the tail end of a bout of vertigo, and I was scared of taking anything psychoactive when the symptoms were subsiding anyway.

The trip to Mercy Neurology was recommended because of the stranger symytoms I mentioned above. The nails-on-the-board, the beam of corrupt information - these things hinted that there may be something wrong with my noodle. But the battery of tests didn’t turn up anything, and my MRI scans looked normal.

In summary, the treatment from June through August was kind and caring, but didn’t make much progress in clearing up the symptoms.

The Fix

As it happens, my wife studied the neurons of the vestibular system1 and the hair cells of the utricle2 in her doctoral and postdoc labs, which were hospital-affiliated. She managed to use some of her connections to get me an appointment at Johns Hopkins Otolaryngology. I’ll add that she did this without much help from me - in a typical partners dynamic, I was resistent to seeing more doctors after having had so little success in the past.

I’m grateful she did, though. Becuase the doctor I saw, Yuri Agrawal, finally diagnosed the issue and solved it during the office visit with the Epley maneuver.

I noticed the impact when I left the office and got into my car. I was between episodes at the time - I thought that I felt mostly fine, not dizzy. In truth, I had adapted to much of the vertigo. And after the treatment, all of the residual symptoms that I had gotten used to disappeared. I felt like I could perfectly focus on distant points. I could move my head around quickly and easily focus on several objects a second (during a dizziness episode, I couldn’t drive; between episodes, I drove rigidly, giving myself lots of extra time before making turns, since it took longer for me to look around at all the surroundings). The general sense of “displacement” was gone. It had been 5 months since I started feeling bad, and now, I felt like I had super-powers. There was a lot of happy giggling on my solo drive home from Hopkins Medical.

Thank you, Dr. Agrawal!

Disclaimer

This blog post may sound like medical advice. I really want to emphasize - I’m not a doctor. I have no idea how common BPPV is compared to other causes of vertigo, so I have no idea how likely the Epley maneuver is to work for you if you’re having vertigo. Talk to a doctor.

During my visit with Dr. Agrawal, which had the fast pacing of a doctor who leads a dual life as head of a research lab, she explained some of the inner ear biology that kicked off my exploration, and recommended I look up Richard Rabbitt, who has done really interesting physical simulation3 of the Epley maneuver.

There are a lot of inaccuracies in my simulation. To get a much better (though not interactive) view of how and why the Epley Maneuver works. You can also meet Dr. John Epley himself!4

I wanted to share my story, and to try out some ideas that had gotten into my head (the vertigo simulator and the interactive Epley model above), in the context of this unpleasant episode in my life.

One takeaway - there can be light at the end of the tunnel, and sometimes although a partner’s involvement in your medical choices can feel a little overbearing, they may often be right. As I tearfully told her after my treatment, since I’m naturally reluctant to see doctors, if she hadn’t been so persistent then I might have gone the rest of my life with on-and-off BPPV.

One Year Later

Since I wrote this posts, a year passed. I’m sad to say that the Epley maneuver wasn’t the end of my Vertigo story. I had 3 more bouts of Vertigo, spaced about two months apart, and leasting for 1 or 2 weeks. Strangely, each episode was followed by strong hearing loss in my left ear. Further trips to Hopkins Otolaryngology lead to no clear diagnosis. My symptoms resemble either Menier’s Disease, BPPV, or vestibular migraine at different times.

To try to get a diagnosis, I’ve been tracking my food, stress and sleep. It seems like sleep deprivation, alcohol or alcohol consumption may be a triggers. I would like to narrow it down, but I recently started a new job and I’m reluctant to do the right experiments to bring on vertigo episodes that interfere with my work and my ability to drive my family around.

On the bright side, now that I’m avoiding all the possible triggers that I’m aware of, it’s been 6 months since I’ve had an episode.

Footnotes

Sodium channel diversity in the vestibular ganglion: NaV1.5, NaV1.8, and tetrodotoxin-sensitive currents on PubMed↩︎

Functional development of mechanosensitive hair cells in stem cell-derived organoids parallels native vestibular hair cells on PubMed↩︎

Wave mechanics of the vestibular semicircular canals on PubMed↩︎

An educational VHS video destribing BPPV and the Epley Maneuver. John Epley gives part of the introduction. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28877495↩︎